When Govanhill Defeated Hate

Taken from Issue 6 of the magazine, which explored the past, present and future of Govanhill, David Jamieson explored what happened when the British Union of Fascists came to the neighbourhood.

By David Jamieson

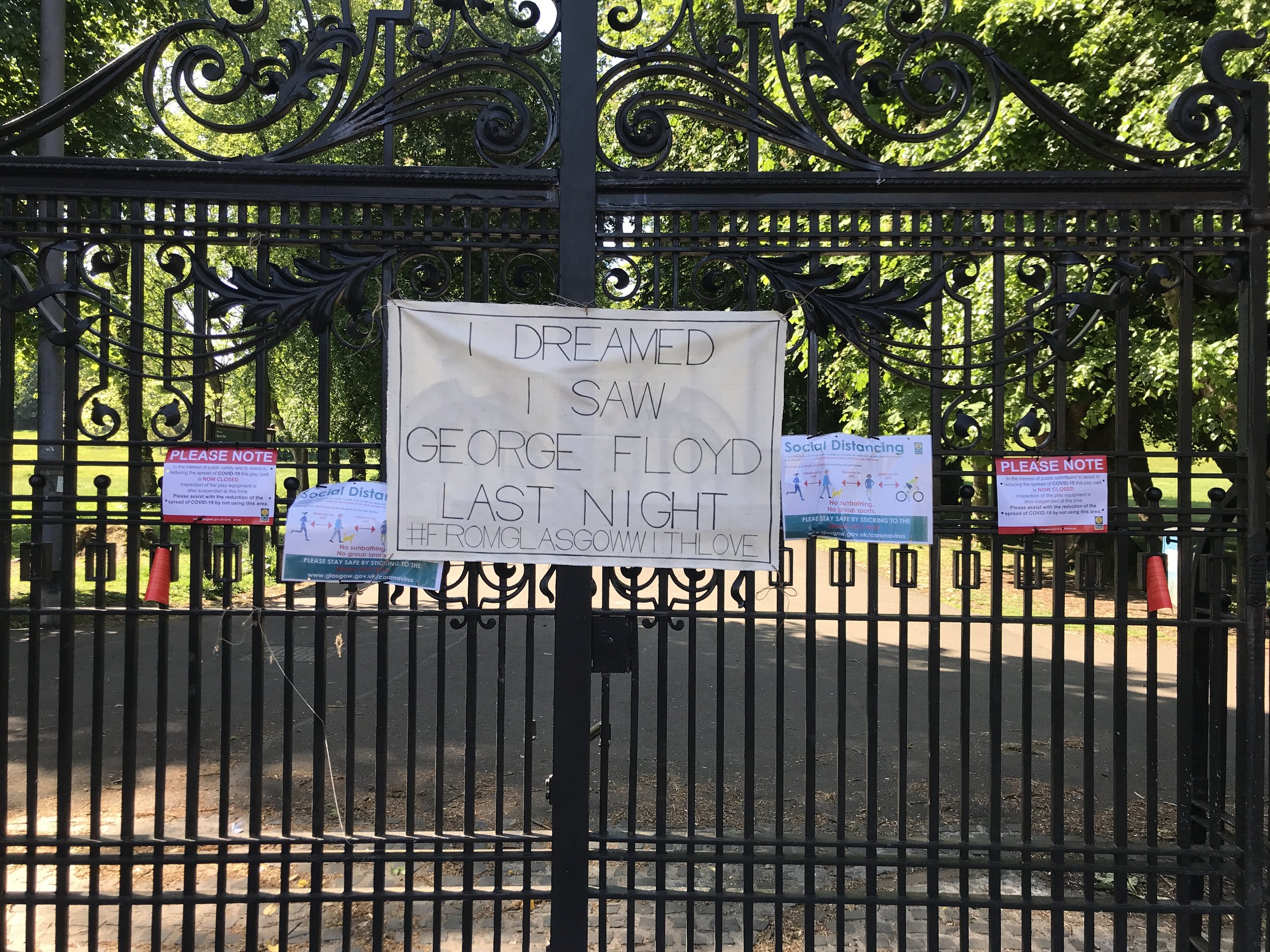

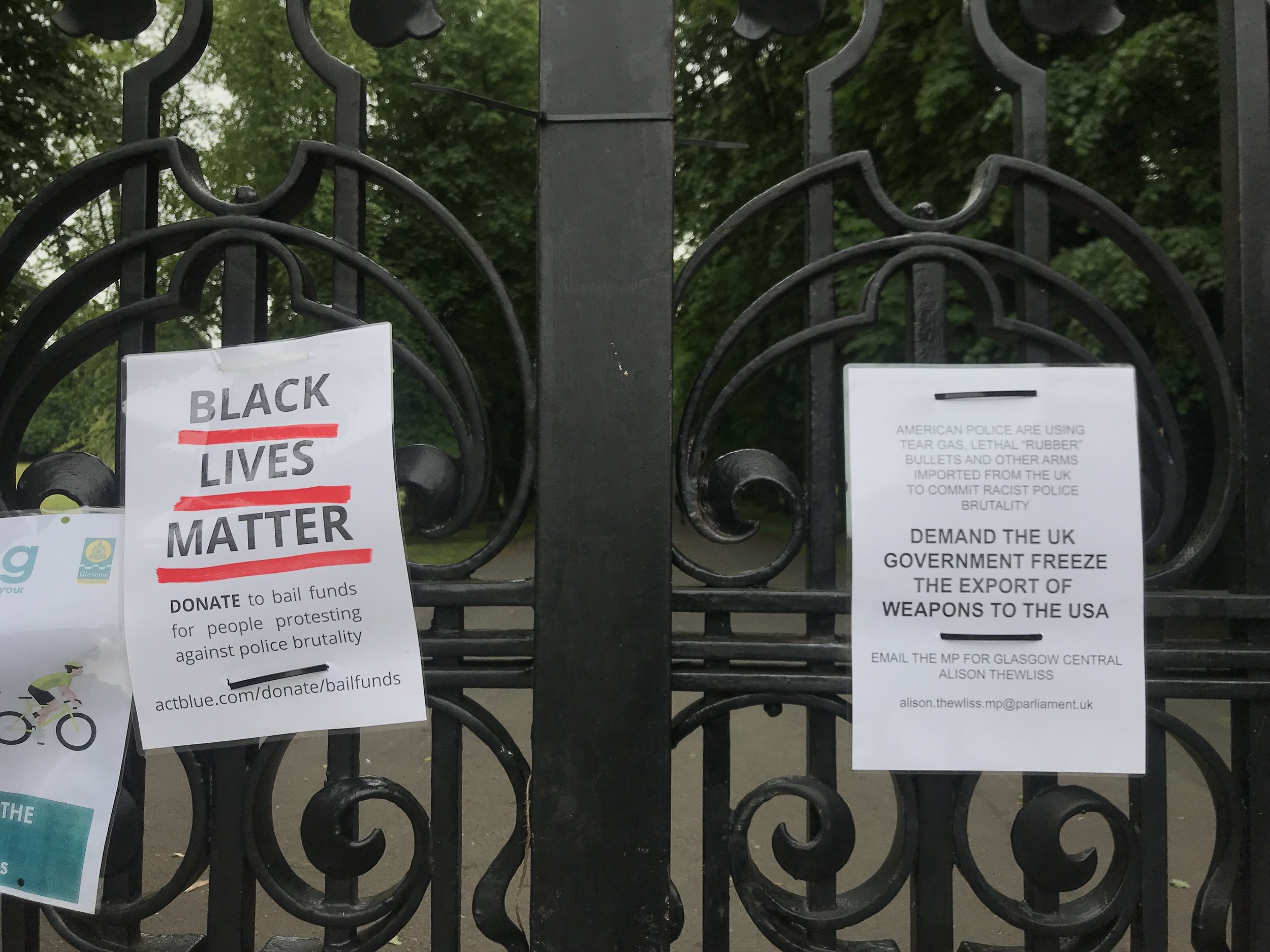

You may have noticed that the gates of Queen’s Park, facing Victoria road, are something of a soapbox. Political messages on a range of issues are frequently plastered across them. It’s the starting point of marches and the site of vigils about everything from climate change to misogyny, police brutality to council cuts.

This isn’t a new function. In the 1930s, as an economic crisis multiplied Glasgow’s unemployment levels and war threatened, the foot of the park became Scotland’s answer to speakers’ corner. Preachers, politicos and orators every description could be found offering their solutions.

It was in this climate of radicalisation that normally peaceful Queen’s Park became a battleground between British fascists and their opponents.

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was founded in 1932 by Oswald Moseley, a charismatic aristocrat who emulated Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany. Its members wore black shirts and used political violence to disrupt left wing opponents. As the 30s progressed, the BUF grew closer to Nazi Germany and became increasingly racist, antisemitic and violent. At its peak, it claimed 50,000 members across the UK.

In Glasgow, the party received establishment backing from the likes of Patrick Boyle, the 8th Earl of Glasgow, and recruited street thugs through Billy Fullerton, a notorious anti-Catholic gangster in the city’s Bridgeton area (who was recently fictionalised in Peaky Blinders). But the organisation remained weak in ‘Red Clydeside’. Its largest hub of support in Scotland was in the rural borders, where it attracted businessmen frustrated by the failing economy.

The surge in party membership coincided with the rising politicisation of society. After the great depression, unemployment and poverty soared. Many workers responded with demands against the rich and powerful, who in turn sought allies from the fascists. But as Hitler increasingly threatened war in Europe the BUF began to lose establishment support. In desperation, Mosley drove local chapters into more provocative and confrontational action – especially targeting Jewish communities.

The Glasgow BUF chapter was part of this drive. It had suffered years of constant harassment by an alliance of socialist, trade unionist and Jewish radicals. Every activity by the party was disrupted by groups of young workers, motivated by a fear of the rising tide of European fascism. These efforts had kept the BUF small and isolated in Glasgow, and it only had around 100 members.

Determined to raise their profile, the Glasgow branch invited one of the BUF’s most notorious and fiery speakers – William Joyce. He was a leading figure in driving the party in an ever more antisemitic direction.

Most of Glasgow’s thousands of Jews lived in the Gorbals area, north of Govanhill which also had a smaller Jewish community. These populations were swelling as Jewish refugees fled into the city from Nazi Germany. This is probably why the BUF chose Govanhill as an area for agitation. They hoped to sow division where communities were mixed, and incite violence against Jews.

When Joyce came to speak at the gates of Queen’s Park, he found his blackshirts outnumbered by young communists, trade unionists and members of a remarkable organisation called the Workers’ Circle – groups of young working class Jews who organised cultural events alongside trade unionism and political action.

Professor Henry Maitles, a Scottish historian who interviewed surviving participants of Glasgow’s thriving 30s anti-fascist movement, tells of how one protester, Monty Berkeley, destroyed the stage set up for Joyce by removing the legs. He then had to make a run for it, being chased by the police – but got away.

The years after the confrontation in Queen’s Park vindicated the stand of the anti-fascists. Some of them were veterans of the fight for the Spanish Republic, besieged by a fascist-aligned military coup supported by Italy and Germany. They would go on to provide aid for Spain’s underground and refugees. As they engaged in this solidarity, the aristocrats and press barons who had initially backed Mosley’s blackshirts continued to press for peace with the fascist powers.

Disillusioned by the failure of the BUF to break resistance in Britain, Joyce placed his faith in a victory for Hitler. When the second world war broke out, he moved to Germany and began broadcasting propaganda for the regime, specifically for the British public. He was hanged for treason at the war’s end.

Govanhill held on through six grim years of war. Though it escaped the worst of the bombing raids in Scotland, which mostly targetted industry in the Clyde area, it was hit by incendiary bombs. Residents built shelters, and survived rationing and war labour at home while many of the area’s young men were sent to fight abroad.

Today, the fight against hate by residents of Govanhill and Glasgow is a powerful reminder of the need to protect our diverse communities through unity in action.