City of Empire: Q&A with curators of a new exhibition unveiling Glasgow's colonial legacy

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum is home to a new permanent exhibition - City of Empire. An empowering display that unpacks Glasgow’s colonial history. In this article, we learn more about the display from the team that put it together.

By Samar Jamal | Photos by Miriam Ali

In our next issue, Talking My Language, we delve into how language keeps us connected whilst constantly evolving. We also look at its diversity, not only in spoken form but also in our actions.

In one feature, Zara Grew, looks at the language of decolonisation – interviewing, Sehar Mehmood, one of four young people from Our Shared Cultural Heritage (OSCH), who are behind City of Empire, a permanent exhibition at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. The exhibition unpacks Glasgow’s colonial history, through artefacts chosen and researched by the young people.

Talking My Language will be out on Friday. Keep an eye out for copies at local cafes and community spaces. In the meantime, we wanted to delve deeper into the exhibition, speaking with curators, Miriam Ali, Meher Waqas Saqib and Kulsum Shabbir and their intentions with creating it.

What were you looking for when selecting items from the Glasgow Museums Resource Centre to feature in the exhibition?

Kulsum: I decided to narrow my focus to objects that specifically implicate Glasgow in its involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

Meher: I wanted to showcase a variety of South-Asian art forms, as well as use them to convey important historical points, such as female activism, and the exploitation and lack of recognition encountered by artists and craftspeople.

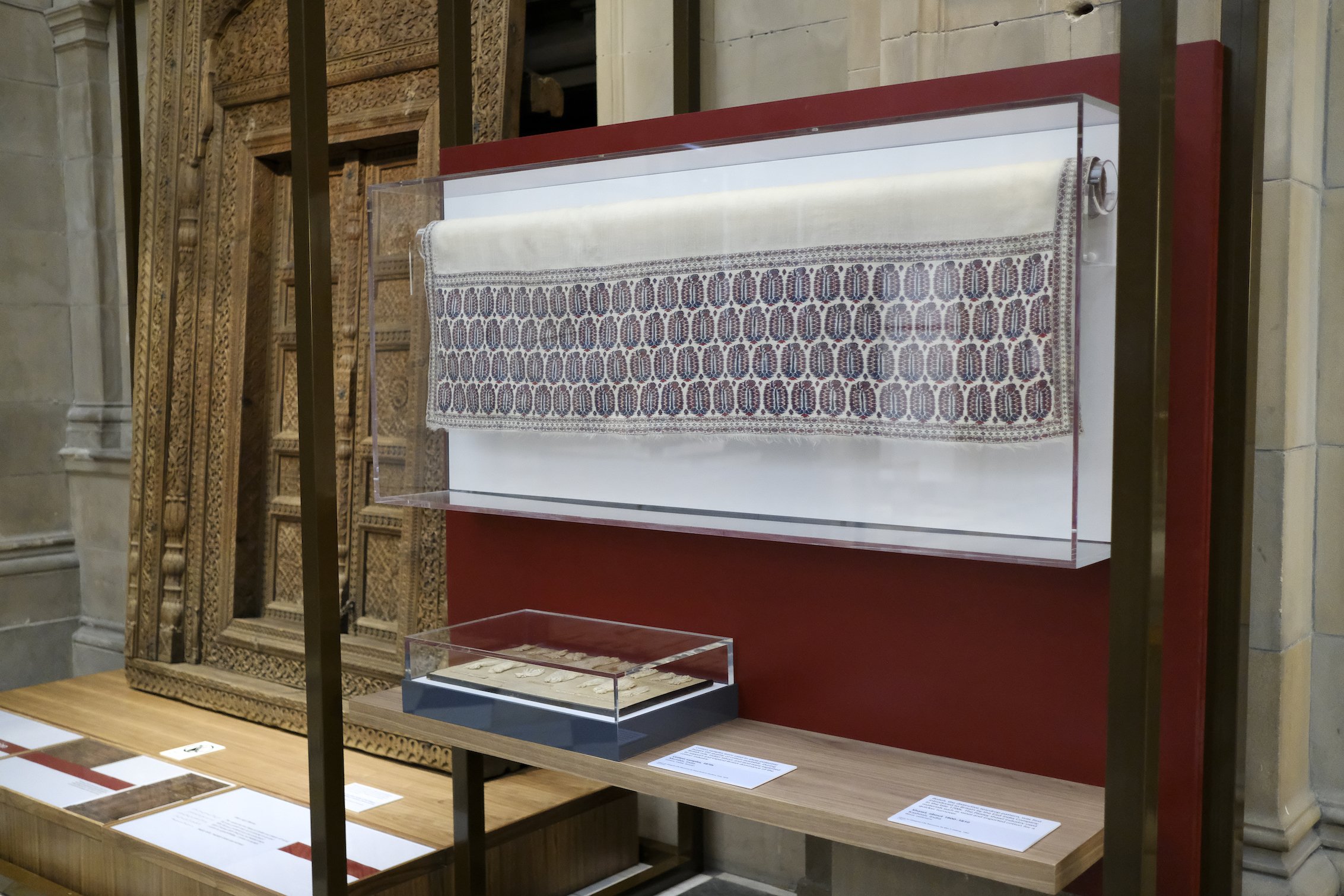

Kashmiri shawl from early 1800s

Miriam: I was particularly interested in finding objects from the time the British Empire was in India, so I could make clear the exploitation of land and resources that Britain had committed in India. When I saw the cotton samples during the tour, I was fascinated by the way they had been preserved from the day they were made, showcasing the different supplies of cotton for trading. From this selection, I wanted to speak on the environmental devastation caused by British colonisation and selected objects that could showcase this.

Tell me a bit more about what your selections tell us about Glasgow's role as a ‘City of Empire’ and its colonial history.

Decorative Door from 1888

Meher: The decorative door for me was a perfect representation of the two-faced nature of British colonialism. When you first look at the door you see a beautiful and intricately carved piece, with extreme attention to detail. But the back side of the door is made of textile crates used to export textiles from British India by Scottish firm James Finlay and Co. Shashi Tharoor, in his book, Inglorious Empire, states “India’s share of the world economy was 23 percent, as large as all of Europe put together (It had been 27 percent in 1700)… By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over three percent. The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India.” This issue is not addressed properly in Scotland and we as Scots must face that much of the development and progress we benefit from was achieved by the systematic looting and destabilisation of much of the Global South.

With the Rani of Jhansi, the leader of the Indian mutiny between 1857-1858, I wanted to focus on female activism, particularly that of women of colour. I think the perception of the West towards women of colour is so often one of docility and submissiveness, and I wanted to challenge that point with historical examples of female activism in the Global South. I did a class on ‘heroic women in literature’ as part of my university degree and not one woman of colour was included. There are countless examples of heroic women from the Global South, such as Nanny of the Maroons, who we hardly hear of.

Miriam: It was great to learn more about the textile industry not only in India but also the effects this had on the Scottish textiles and fashion industries. I began to look for Kashmiri shawls in the collections navigator and found a beautiful Kashmiri shawl from the early 1800s, pre-British rule.

Kashmiri Shawls are beautiful and intricate textiles, often featuring the boteh (a motif in ornaments characterised by a sharp-curved upper end, resembling either an almond or a pine cone shape, or ambi (mango motif) pattern. They could take Kashmiri weavers up to two years to make. They were imported from Kashmir to Britain by the East India Company in the late 1700s. As they were so expensive to produce and ship, many cities in Europe began to reproduce the shawls, often using cheaper and faster methods. One city that became very successful in this industry was Paisley, which is why we now know the iconic boteh pattern as the Paisley pattern. I believe it is important that the legacy of this pattern is known and not overshadowed by the vast consumerism which led to the success of the pattern in the West.

When you were researching these items, was there anything you found that particularly stood out?

Kulsum: I found little to no information about the tobacco pipe. I felt that this was a reflection of the dehumanisation of enslaved Black people who had their history erased. For the label of this object, I decided to write a short poem from the point of view of the young man depicted, giving a voice to his frustration and strength. The research process for this display could often feel clinical and removed, and being allowed to explore the emotional aspects of such histories was cathartic in a way, and a huge responsibility.

Meher: While exploring Rani of Jhansi's role in the Indian Mutiny of 1857 as a part of the Indian resistance forces, I discovered that the individual leading the British forces against this ‘uprising’ was Colin Campbell, a Scotsman. This underscores the significant and central role that Scots played in British colonial pursuits, shedding light on their deep complicity and leadership in these historical endeavours.

Miriam: The physicality of the object is what stood out to me the most. It felt different to a piece of art as it had a direct link to the farmer of the cotton and the weaver who made the twists. I couldn't find anything behind the process of creating cotton samples and where and when they would have been used but I found the lasting detrimental effect Britain’s trade of Indian cotton has made on India's agricultural environment.

What is unique about this exhibition?

Kulsum: Being involved as a young South Asian person, this experience was invaluable. I gained so much knowledge and experience working on the project, which is exactly the reason I joined OSCH in the first place and I think this is what makes the display so unique. We each brought so much of our personal experience to the project, and I feel that the passion we have for our work is palpable and can be seen throughout the exhibition.

Meher: The addition of cultural aspects, like Urdu poetry into the exhibition is something not done before in a Glasgow Museums exhibition, and this was very exciting for us as it opens the exhibition up to a whole new demographic that may have not visited museums due to accessibility issues.

What do you think audiences can gain by viewing museums through a colonial lens?

Meher: I hope that it serves as a moment of deep reflection and as a true learning tool. We wanted this whole project to encourage people to view the history of Glasgow in a different way, that acknowledges the struggles and exploitation of people of colour. For people of colour visiting the display, I hope that it brings a sense of familiarity and true representation that has been absent in museums. I would have loved to go into a museum as a child and see my cultural heritage being talked about in a positive light, and truly this project was designed to inspire and educate all people, but especially children. Many issues discussed in the display serve as starting points so viewers are exposed to these issues and can then learn more about them which ensures that the museum serves as an educational space for all.

Miriam: During a visit with my family, I saw another South Asian family visiting the display. I could see a boy call his mother to come and read something and from what I gathered he was excited to show her the Alama Iqbal poem written in Urdu, next to the Rani of Jhansi statue curated by Meher. This seemingly small interaction is one of the many things we wanted to achieve by being part of this project.