Peek into the Past: Life in Govanhill during World War II

Born and bred Govanhillian Arthur Oliver has previously written for us about growing up in the area in the 1930s. Arthur continues his local history tour of Govanhill with a personal account of how the area changed during WWII.

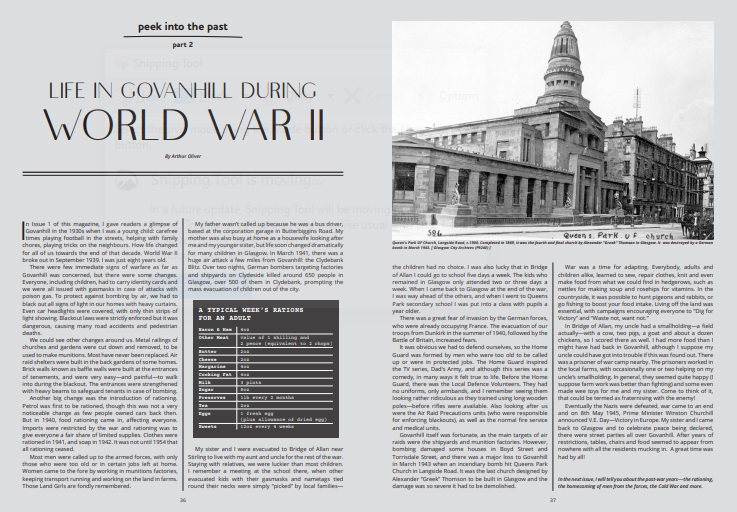

Queen's Park UF church, Langside Rd, c.1900 Completed in 1869, it was fourth and final church by Alexander "Greek" Thomson in Glasgow. It was destroyed by a German bomb in March 1943. | Credit: Glasgow City Archives (P9240)

By Arthur Oliver

In my previous piece, I gave readers a glimpse of Govanhill in the 1930s when I was a young child: carefree times playing football in the streets, helping with family chores, playing tricks on the neighbours. How life changed for all of us towards the end of that decade. World War II began in September 1939, when I was just eight years old.

There were few immediate signs of warfare as far as Govanhill was concerned, but there were some changes. Everyone, including children, had to carry identity cards and we were all issued with gas masks in case of attacks with poison gas. To protect against bombing by air, we had to black out all signs of light in our homes with heavy curtains. Even car headlights were covered, with only thin strips of light showing. Blackout laws were strictly enforced but the blackout was dangerous, causing many road accidents and pedestrian deaths.

Read about growing up in Govanhill in the 1930s here

We could see other changes around us: metal railings at churches and gardens were cut down and removed, to be used to make munitions. Most have never been replaced. Air raid shelters were built in the back gardens of some homes. Brick walls known as baffle walls were built at the entrances of tenements, and were very easy – and painful – to walk into during the blackout, and the entrances were strengthened with heavy beams to safeguard tenants in case of bombing.

Another big change was the introduction of rationing. Petrol was first to be rationed, though this was not a very noticeable change as few people owned cars back then. But in 1940 food rationing came in, affecting everyone. Imports were restricted by the war and rationing was to give everyone a fair share of limited supplies. Clothes were rationed in 1941, and soap in 1942. Bread was put on the ration in 1946, after the war ended, and it was not until 1954 that all rationing ceased.

A typical week’s rations for an adult:

● Bacon & ham: 4 oz

● Other meat: value of 1 shilling and 2 pence (equivalent to 2 chops)

● Butter: 2 oz

● Cheese: 2 oz

● Margarine: 4 oz

● Cooking fat: 4 oz

● Milk: 3 pints

● Sugar: 8 oz

● Preserves: 1 lb every 2 months

● Tea: 2 oz

● Eggs: 1 fresh egg (plus allowance of dried egg)

● Sweets: 12 oz every 4 weeks

Most men were called up to the armed forces, with only those who were too old or in certain jobs left at home. Women came to the fore by working in munitions factories, keeping transport running and working on the land in farms. Those Land Girls are fondly remembered.

My father wasn’t called up because he was a bus driver, based at the corporation garage in Butterbiggins Road. My mother was also busy at home as a housewife looking after me and my younger sister, but life soon changed dramatically for many children in Glasgow. In March 1941, there was a huge air attack a few miles from Govanhill: the Clydebank Blitz. Over two nights, German bombers targeting factories and shipyards on Clydeside killed around 650 people in Glasgow, over 500 of them in Clydebank, prompting mass evacuation of children out of the city.

My sister and I were evacuated to Bridge of Allan near Stirling to live with my aunt and uncle for the rest of the war. Staying with relatives, we were luckier than most children. I remember a meeting at the school there, when other evacuated kids with their gas masks and name tags tied round their necks were simply “picked”; by local families – the children had no choice. I was also lucky that in Bridge of Allan I could go to school five days a week. The kids who remained in Glasgow only attended two or three days a week. When I came back to Glasgow at the end of the war I was away ahead of the others, and when I went to Queens Park secondary school I was put into a class with pupils a year older.

A commemorative plaque at Glasgow Central Station | Credit: Thomas Nugent, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons License

There was a great fear of invasion by the German forces, who were already occupying France. The evacuation of our troops from Dunkirk in the summer of 1940, followed by the Battle of Britain, increased fears. It was obvious we had to defend ourselves, so the Home Guard was formed from men who were too old to be called up or were in protected jobs.

The Home Guard inspired the TV series Dad’s Army, and although this series was a comedy, in many ways it was true to life. Before the Home Guard there was the Local Defence Volunteers. They had no uniforms, only armbands, and I remember seeing them looking rather ridiculous as they trained using long wooden poles before rifles were available. Also looking after us were the Air Raid Precautions units who were responsible for enforcing blackouts, as well as the normal fire service and medical units.

Govanhill itself was fortunate, as the main targets of air raids were the shipyards and munition factories. However, bombing damaged some houses in Boyd Street and Torrisdale Street, and there was a major loss to Govanhill in March 1943 when an incendiary bomb hit Queens Park Church in Langside Avenue. It was the last church designed by Alexander “Greek” Thomson to be built in Glasgow and the damage was so severe it had to be demolished.

War was a time for adapting. Everybody, adults and children alike, learned to sew, repair clothes, knit and even make food from what we could find in hedgerows, such as nettles for making soup and rosehips for vitamins. In the countryside it was possible to hunt pigeons and rabbits, or go fishing to boost your food intake. Living off the land was essential, with campaigns encouraging everyone to “Dig for Victory” and “Waste not, want not”.

VE Day by LS Lowry. This painting can be seen at the Kelvingrove Museum in the West End | Credit: Damian Entwistle, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons License.

In Bridge of Allan my uncle had a smallholding - a field actually - with a cow, two pigs, a goat and about a dozen chickens, so I scored there as well. I had more food than I might have had back in Govanhill, although I suppose my uncle could have got into trouble if this was found out. There was a prisoner of war camp nearby. The prisoners worked in the local farms, with occasionally one or two helping on my uncle’s smallholding. In general, they seemed quite happy (I suppose farm work was better than fighting) and some even made wee toys for me and my sister. Come to think of it, that could be termed as fraternising with the enemy!

Eventually the Nazis were defeated, war came to an end and on 8th May 1945 Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced V.E. Day – Victory in Europe. My sister and I came back to Glasgow and to celebrate peace being declared, there were street parties all over Govanhill. After years of restrictions, tables, chairs and food seemed to appear

This article first appeared in issue 2 of the magazine. If you missed it, you can order your copy here.