It’s Criminal at the Tron Theatre

The one time show, It’s Criminal was a thought provoking performance which forced the audience to consider how crime is reported and the impact it has on people and communities.

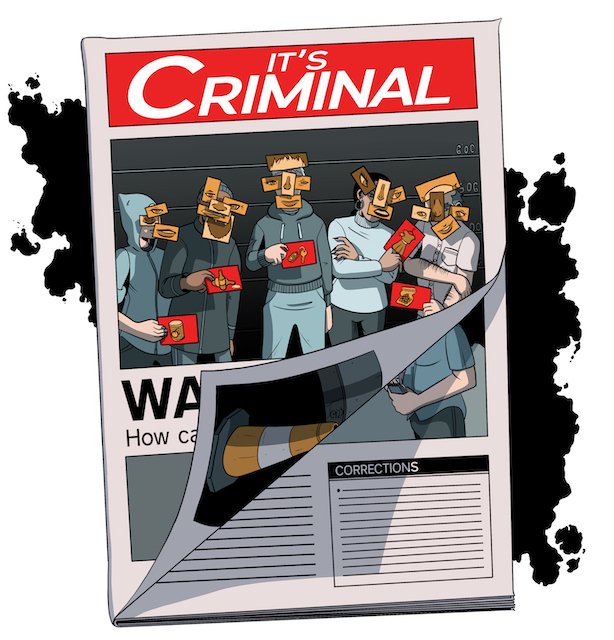

By Samar Jamal | Illustration by Chris Lau Manson

It’s Criminal created a much-needed conversation, asking the important questions of: “How can we change the landscape of crime reporting to reduce harm?”

The performance was the culmination of a participatory research project led by Rachel Hamada, an investigative journalist and one of the co-founders of The Ferret. The project aimed to understand people's experiences in the criminal justice system and the long-term harmful effects of media reporting. It also explored the way certain communities have been stigmatised by the media.

The storytelling project was a collaboration between Contemporary Narratives Lab, The Ferret and Greater Govanhill magazine and supported by City University of London’s Higher Education Innovation Funding Knowledge Exchange. The research focussed on people from Glasgow and particularly Govanhill, which has often been demonised by certain sections of the media.

The show itself portrayed a day in the newsroom where writers scour to find local stories but, more worryingly, find stories that can be exaggerated and sensationalised to increase readership and profits. It did not shy away from calling attention to the media's responsibility when it comes to fear mongering.

“The worst time of my life was narrated by everyone but me” is a testimony from the research read out by one actor.

This statement highlights how the media often controls the narrative. By failing to discuss events with the people at the centre of the stories they are prevented from having any dialogue and providing readers with an expansive account of events.

The show also wanted to highlight the realities of the justice system and the people who are framed as guilty. As one actor explained: “You have a nine in ten chance of being convicted if you go to trial”. This results in people forfeiting their chance to prove their innocence, consequently being labelled guilty.

Everyone involved in the play had been affected by crime reporting in different ways, creating solidarity between the cast and research participants. Tabitha Dearie, one of the actors said:

“At first I was just really taken off guard with how many people there were and how much we had all experienced the justice system in our own way. And it wasn't like I did this and you did this, It was more like what the media is doing to us.”

For Rachel, the diversity in the cast was critical to bringing people with a variety of experiences together and changing the landscape of crime reporting:

“A lot of my job is learning from other people's work and collaborating. In my travels, I saw that they were doing a lot of interesting work in the US with regards to reframing crime reporting so it's less about crime and justice and more about community safety. And it's more so to make things better for the people living in the neighbourhood rather than to sell papers and have the sensationalist factor.”

One of the aims for this project was to open up a conversation which may lead to changes in the way journalists build trust with communities and report crime. Rachel explains:

“You want to change things and create impact and even if that’s just a couple conversations in the newsroom, that's great. There's also practical things which could develop like potentially working with student journalist departments and thinking about how journalism courses can train people to report more holistically on what's happening, instead of just this hero-villain narrative.”

Rachel also wanted the performance to encourage the audience to question their role and why, as readers, we are so attracted to sensational stories as well as the consequences this has for the people we read about. “I think there’s something with crime that it's particularly distorted”, she said. “Reading shocking crime headlines can appeal to quite a dark side of our human nature. And it's easy to keep feeding that.”

Although readers may only spend five minutes reading a story, within that time stereotypes and beliefs are formed which scapegoat the subject and leave them with a lifelong damaged reputation.

The performance finished with a discussion between the cast and the audience. Questions were posed to the audience such as: “How can we change the way crime is reported?” and “Would you trust the media to report in your community?” This led to a constructive conversation about where we need change and how we achieve it.

It’s Criminal is just the beginning of the conversation. Rachel hopes that with further funding for shows and research, there can be a serious shift in crime reporting:

“There are the little cultural changes that can start to make a difference. I'm kind of optimistic overall, but this is quite a big beast to combat, so it will take time. But hopefully at least we started a conversation, which was really the intention.”

For further reading on the landscape of crime reporting and additional resources click here.